|

|

The idea of building a permanent rail link

between Burma through Thailand to China

was first raised in the 1880's by the British colonial authorities in Burma. The

route considered was between Phitsanoluk in

northern Thailand (then

the Kingdom of Siam)

and Moulmein in Burma.

However no investment was forthcoming and the idea was shelved.

As early as 1939, Japanese agents in Thailand were preparing the ground for the

construction of the railway, once Japanese forces had taken control of South-East Asia. The railway was intended purely as a

strategic military supply line for the movement of troops and equipment to

the Burma Front, and ultimately for the invasion of India.

The Japanese had originally intended to

use an Asian workforce to construct the railway, and indeed most of the

railway labourers were from Burma, Java and Malaya

- some 240,000 seems to be the most reliable estimate. However with the fall

of Malaya, Singapore

and Indonesia

(then the Netherlands East Indies) in 1942, the occupying forces found

themselves with a large number of prisoners of war, an event they had not

planned for. What to do with these prisoners was a vexed question for the

Japanese military administration for the first few weeks of their rule. It

was then decided that these men - skilled, disciplined military personnel -

were to be used to further the Japanese war effort.

Gradually the PoWs

were grouped into 'Forces' and sent to work on various projects. Some went to

Japan to work in mines and construction gangs, others to Saigon to do dock

work, and still others to various parts of the newly created 'Greater East

Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere'. The first group of PoWs who were ultimately to work on the railway,

were those of 'A Force'. These 3,000 men were sent by ship to from Singapore to various places in Burma to work

on airfield construction. Later in 1942 these isolated groups were

concentrated at Thanbyuzayat to begin work on the Burma end of

the railway. Construction began in June 1942, under the direction of the

Imperial Japanese Army's 5th and 9th Railway Regiments. Gradually more forces

were sent to Burma and Thailand; in

total more than 60,000 prisoners of war were transported to the railway

project during 1942-3. At the same time the 'Sweat Army' of labourers from Burma, ostensibly volunteers but

many conscripted by the puppet Burmese government, toiled on the construction

work. Conditions in Malaya after the capitulation of the Allies caused the

collapse of agricultural production, forcing many undernourished Malayan

plantation workers - mostly of Tamil extraction - to volunteer for work on

the railway, the terms being "A dollar and a pound of rice per

day". Many went purely for the rice.

The 415km line linking the Thai and

Burmese railway systems was constructed simultaneously from both ends, Thanbyuzyat in Burma

and Nong Pladuk in Thailand. The

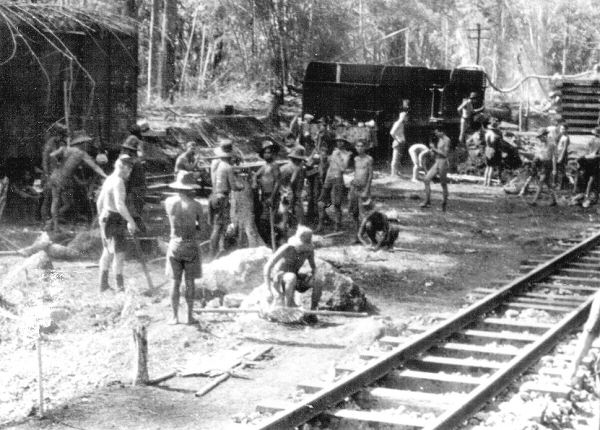

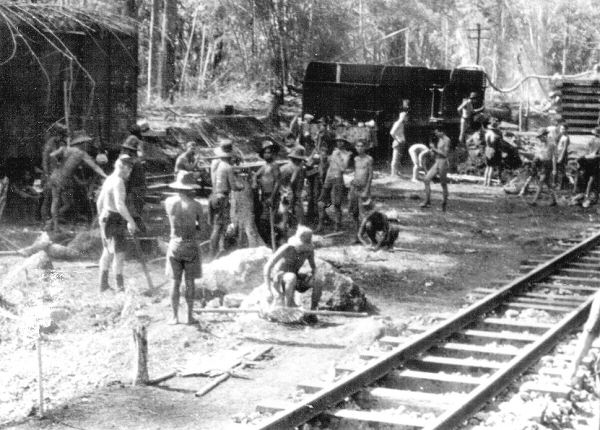

appalling conditions for those working on the railway are well documented

elsewhere. The numbers of deaths speak for themselves. Disease (particularly

dysentery, malaria, beriberi and savage cholera epidemics), starvation

rations, overwork, poor or no accommodation or sanitation, and the individual

brutality of Japanese and Korean engineers and guards, took their inevitable

toll. Over 13,000 prisoners of war perished during the period between late

1942 and late 1945. The numbers of deaths of the Asian labourers

is harder to calculate; around 100,000 seems to be

the most reliable figure. During the infamous 'speedo'

period, July to October 1943, the desperation of the Japanese engineers to

finish construction on time, under severe pressure from their superiors in Tokyo, meant that many

men were forced to do grinding manual labour around

the clock - 62 hours work out of 72 hours appears to be the record. Rest days

were rare. This, combined with the first outbreak of cholera, caused the

death toll to reach its peak during this time.

The Thai and Burmese sections of line were

joined near Konkoita in October 1943. Actual

construction took a mere sixteen months - some would say a remarkable

engineering feat. After the line was completed all of the PoWs

were transferred from remote jungle camps to base camps and hospitals. Some,

after recovery, formed new work parties destined for Japan, others returned to Singapore. A

large number of PoWs remained in the Thailand base

camps until the end of the war.

The majority of the Asian labourers remained in the jungle camps to operate the

railway under Japanese command, and to undertake maintenance work on the

line. From time to time PoW work parties were taken

back onto the line to carry out maintenance work and cut wood fuel for the

locomotives. This work became crucial to the Japanese; the situation on the

Burma Front was becoming critical for them and their vulnerability in the

waters of the South China Sea meant that the

railway was a vital supply route that had, at all costs, to remain

operational. An average of six trains per day operated for the life of the

line, well below original Japanese expectations but still a major

contribution to their strength on the Burmese Front.

The railway continued to operate, with

some interruptions, until the final victory of Allied forces in August 1945.

Slowly the prisoners of war and Asian labourers

were rehabilitated and returned home. Some former PoW's

remained in Thailand and Burma to

recover their comrades from remote maintenance camps, and to work on grave

recovery parties. The railway then fell into disuse through lack of

maintenance, and in 1947 the line and rolling stock were sold to the Thai

Government. The money being used for war reparations and to compensate those

countries who lost rail stock to the Japanese. By

1957 the Thai government re-opened the section of line from Nong Pladuk to Nam Tok (known during wartime as Tha

Sao), and this part of the railway still operates today. Much of the

abandoned section has now been reclaimed by the jungle, but embankments,

cuttings and bridge sites can still be found

Top of Page

|